Photo by Ryan Moreno on Unsplash

I’m not often at a loss for words when it comes to writing my way into an essay, or more broadly, into the world. I have an architect’s arrogance: claiming space with words and sentences and paragraphs that construct a room then a home then a labyrinth that I assume you, Dear Reader, will wander in happy agitation. That’s what we writers do, isn’t it? A coup d'etat as we fill your head with our voices?

Subclinical Graphomania: I am forever scrawling my thoughts on legal pads, receipts, paper scraps, or the back of my hand, rudely halting a conversation with a friend to write what is pressing RIGHT NOW on a napkin (which, in the end, is not so pressing as I will absentmindedly leave the wadded napkin behind), or “Yes, yessing” my mother on the phone as I try to type on my computer without her hearing the rapid fire click-clicking of keys, or veering off the highway onto the shoulder to scratch down the opening sentence for a story which has arrived via God’s lips to my distracted driver’s ears, or, simply sending myself a voice text while drifting between lanes.

I've been thinking about the ways I have tried to fit myself into the constricting expectations of boyfriends and a husband, teachers, and friends. Mostly men. And how men have told me (and I have too often and too willingly believed their words without critical analysis) that I am too much — too noisy, too brash, too outspoken, and that I need to lower my voice, tone it down, shrink myself.

Words fomenting in my brain, words foaming at my mouth, words following words on my tongue. My talking to myself wakes me in the middle of the night, so I reach for my journal, and when I can’t find it (because it’s dark and because I don’t have an actual journal anymore), I take pen to forearm and write the words that woke me from my silent sleep: like speaking through a jaw wired shut. May Sarton remarks in Journal of Solitude, “It may be outwardly silent here but at the back of my mind is a clamor of human voices, too many needs, hopes, fears. I hardly ever sit still without being haunted by the “undone” and the “unsent.” Or, I might add, sleep through a night without being haunted by the unwritten.

Once upon a time, I used to cut my forearms with Xacto blades, broken glass, and knives, anything sharp and within reach, a way to write into my pain. My therapist gave me a black Sharpie and told me to write better words onto my skin: love hope redeemed.

Paradoxically, this essay’s subject, on voice and agency, has kept me silent for days. My inner voice, always a reliable critic, has relentlessly undermined my confidence, casting aspersions: Who do you think you are to presume that anyone wants to hear what you have to say? Why does anyone other than your dog, HoneyBea, need to hear from you? Walk? Treat? Eat? All the words you need.

Who do you think you are?

My parents used to say this to me when I’d get in trouble for defiantly mouthing off in adolescent anger. It wasn’t a real question, and I wasn’t supposed to answer all the questions inside the question: Who do you think you are to talk to us like that? To dare question our authority? To dare speak as if you have a right to speak?

So I clenched my teeth and pressed my lips together, wiring my jaw shut, but answering back still in my tumultuous silence, words clamoring inside of me, clawing at the back of my throat: I think I am smart and funny and angry and lonely and tired of having to be someone that I am not and I can’t bear to fucking imagine swallowing my answer but I know this is what I will do, this is what will be expected of me for many many years because I am a girl.

Silenced. Because I was a girl. Not always and not from the start.

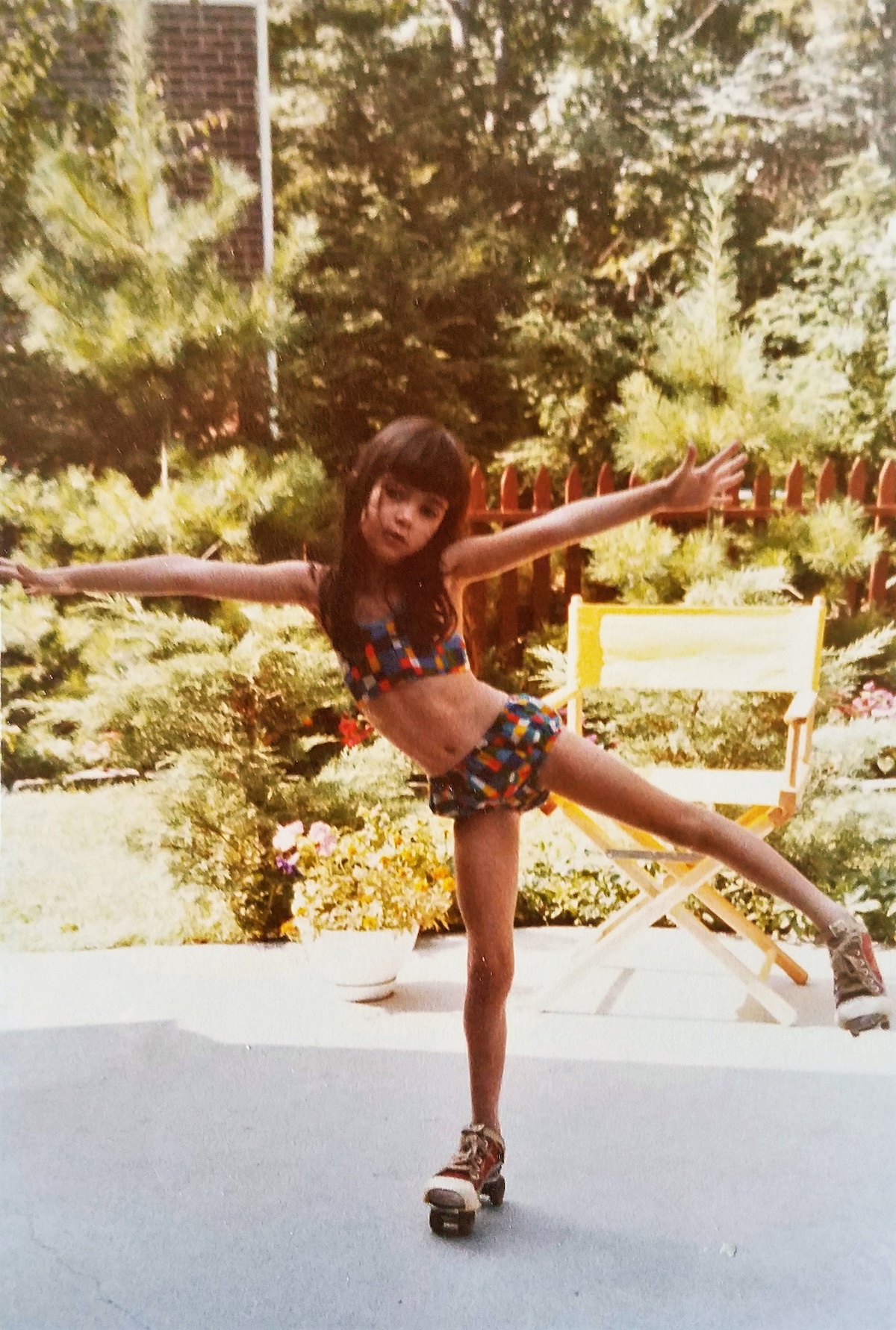

This photo of me at five?

I was loud and sure of myself and didn't give a damn about anyone's expectations other than my own, and didn't even know to care about what boys and men might think of me because I was in love with Wonder Woman. I never raised my hand or waited my turn to speak. Early elementary school report cards note my “excellent grades” but also that I was a “chatterbox,” to which I freely admit: I was a smart pain in the ass, side commenting, whispering, talking, talking, talking to the teacher during quiet time because I had questions and answers and complaints and wanted to be noticed, to be seen, to be heard.

In ballet class, my stern, elderly Russian instructor tapped my skinny calves with her yardstick because I joked around during our warm-up at the barre, and when that didn’t quiet me — I just had so much to say and needed to say it now not later! And couldn’t we skip the slow dégagés for the fast dégagés or skip right to the frappés? — she sent me into the dressing room to “gather myself.” I sat cross-legged under the rack of pink tutus and peaked between the curtain at the quiet, disciplined girl ballerinas, listening to the metronomic shush of their leather soled slippers glissé-ing across the floor while my body flooded with hot shame.

Who do you think you are?

Nobody. Nobody.

Sometimes I was silenced even when I didn’t make a sound.

Third grade, quiet period: I was sitting in my seat, middle of the row — disciplined reader if not ballerina! — absorbed in Judy Blume’s Deenie, a book about a girl whose mother pushes her into modeling, but then she is diagnosed with scoliosis so must navigate all the complicated body insecurities beyond those of ordinary adolescence, when the boy behind me snickered and grabbed the book.

I turned around, lurching for him, and yelled: “Give me my book back!”

My teacher strode down the aisle, scanned the opened page, and shook her head. My book disappeared into her desk drawer. When my mother picked me up at the end of the day, the teacher waited with the opened book, her finger pointing to a paragraph, then sentences, then words. “She was disrupting the class,” she said. “This book is not allowed in school.”

Disruptive silence. Passive censorship. The offending passage? Deenie says, “I have this special place, and when I rub it I get a very nice feeling. I don't know what it's called or if anyone else has it but when I have trouble falling asleep, touching my special place helps a lot."

Deenie’s revelation offered a comforting confirmation bias for my own silent, in the dark, under the covers exploration and attendant, confused as yet unnamed ecstasy. But lesson learned: my daring to read these words was the problem not the boy’s sneering immaturity. More importantly? I understood that female desire and pleasure, written or spoken, was explicitly and implicitly dangerous and disruptive. Years and years before I could admit to a boyfriend or even to my once husband, that I, too, knew how to turn myself on and bring myself to orgasm. Years and years before I could make any sounds of pleasure or say without shame and with happily earned authority, “Not there but there, and Yes, more and faster now slower now softer now harder.”

You Might Also Like: You Aren't Lazy — You're Just Terrified: On Paralysis And Perfectionism

Recently, an erstwhile lover said, “I don’t think you heard yourself, but you made an otherworldly sound when you came.”

As if I was not only deaf but dumb. “I heard myself loud and clear,” I said. “The same sound I make on my own without need of you.”

I've been thinking about the ways I have tried to fit myself into the constricting expectations of boyfriends and a husband, teachers, and friends. Mostly men. And how men have told me (and I have too often and too willingly believed their words without critical analysis) that I am too much — too noisy, too brash, too outspoken, and that I need to lower my voice, tone it down, shrink myself. Shush shush shush.

After my divorce, a friend told me that my once husband said to her, “Kerry is the moon to my sun, reflecting my light.”

Late night, scotch, and John Coltrane on the record player, so he was a few drinks in, maybe trying to be poetic, but drunk talk emboldens us, doesn’t it? We speak or spill our secrets. Once, drunk myself, I pulled off my wedding ring, threw it at him, and yelled, “I’m done. We’re over.” In the morning, the ring was back on my finger, years before I could say those words sober.

And it starts small: a girl stops risking and raising her hand because she is not only ashamed of giving the wrong answer in math class but of being discounted. She bunches her fists beneath her thighs to remind herself to hold back, to be inconsequential.

In elementary school, I raised my hand to answer every question because, truth be told, I usually knew the answers. Miss C., my fourth-grade dream teacher, not only assigned me extra books to read (The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, A Wrinkle in Time, and Little Women) but invited me to give presentations to the class on them or any subject of my curiosity. My first presentation? King Tut.

The chalk was damp in my sweaty palms because I was terrified I’d misspell A-R-C-H-A-E-O-L-O-G-Y and T-U-T-A-N-K-H-A-M-U-N on the blackboard, but my confidence grew as I told the story of how Henry Carter, ready to give up after years of searching for King Tut’s tomb, discovered it in the very last year of funding. He used a chisel that his grandmother gave him on his seventeenth birthday to tap tap tap through a wall and then raised a candle to the tiny opening. Lord Carnarvon, the man who funded the excavation for almost ten years, was standing beside him and asked, “Can you see anything?”

“And do you know what Carter answered?” I asked my classmates.

Dramatic pause while they waited in rapt silence for my words.

“’Yes,’ he said, ‘wonderful things.’”

I read to them from his own account: “At first, I could see nothing, the hot air escaping the chamber causing the candle flame to flicker, but presently, as my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist, strange animals, statues, and gold—everywhere the glint of gold.”

Yes, isn’t this how words, when placed next to each other, shimmer, then details emerge, as our story grows? In writing and telling our stories aren’t we, like Carter, holding our flames to the dark? Can you see what I am trying to show you? Can you hear what I am trying to tell you?

Oh, but how garrulous exuberance is diminished and shamed. After class, one boy, maybe not so rapt up in my storytelling, elbowed me. “Know it all,” he said. Another whispered, “Teacher’s pet.”

Sheryl Sandberg, COO of Facebook, and author of Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead, believes that the main obstacle between women and success is our lack of confidence in voicing our ideas and opinions and trusting in our wealth of knowledge. “We need to teach women to raise their hands more.”

But what if you raise your hand and the teacher doesn’t call on you?

In eighth grade, Miss P., my math teacher pulled me aside after class and said, “You need to give others, the boys, a chance."

“Why?” I said. “I know the answers, and they don’t.”

She was an ogress. Forgive me a moment of snarky reverie: she wore a uniform of shit brown polyester and orthopedic shoes, a perfect match to her grim, pinched demeanor, and she rapped our desks with her pointer as if summoning us for military exercises. She was a Miss, even in her murky fifties, and in cruel summation, I imagined deservedly so. In retrospect, she was likely underpaid by the Catholic school, exhausted by hyper-pubescent disruptions of algebraic equations, and maybe all the years of being the butt of students’ jokes and seeing our disdain for her corny jokes, of being forever Miss and lonely, had made her cruel, too.

“Who do you think you are?” she asked, “Too smart for your own good and how you walk up to the board all la di da to write out your answers?”

La di da? Didn’t she see how my legs trembled, how I was afraid I’d trip or be tripped on my walk up to the front of the room? Thud. Shame. Silence.

For a few days, I continued to raise my hand, waving as if in distress, but her eyes passed over me and she called on the boys; so I raised my hand as if reaching for something to grasp, something to steady myself, but she ignored me and called on the boys; and then I stopped raising my hand and just wrote out the answers on my paper, right answers most of the time, but less sure of their rightness because in silence, that inside voice was vociferous and doubted my own knowing.

This is how girls grow silent: we question whether anyone wants to hear what we have to say and then assume no one will believe what we say is true.

And it starts small: a girl stops risking and raising her hand because she is not only ashamed of giving the wrong answer in math class but of being discounted. She bunches her fists beneath her thighs to remind herself to hold back, to be inconsequential. Silence is safer than the teasing and taunting. But it is not silence because her inner voice, as a counterweight, is punishing and strident. Instead of flourishing, she withers, and as her daring contracts, a perverse hope grows: Please let me be invisible.

Silent girls become silent women. Or I did, anyway. By high school, I forgot how to speak for myself and burrowed into books, letting Plath, Salinger, Sexton, Marquez, O’Connor, and Cather and and and…speak for me, for my fear and longing, anger and joy. I drank booze to get drunk enough to tell boys that I liked them or hated them, but then, too drunk, forgot to say “No,” or, the next day, couldn’t clearly remember my “Yes.” I cut my arms in a contradictory mute annunciation of pain and consequently, was never able to raise my hand in class, to offer my answer, my idea, or my opinion for fear that my sleeve would slide down my arm, and my teacher and classmates would see the wounds and scars that crisscrossed my skin.

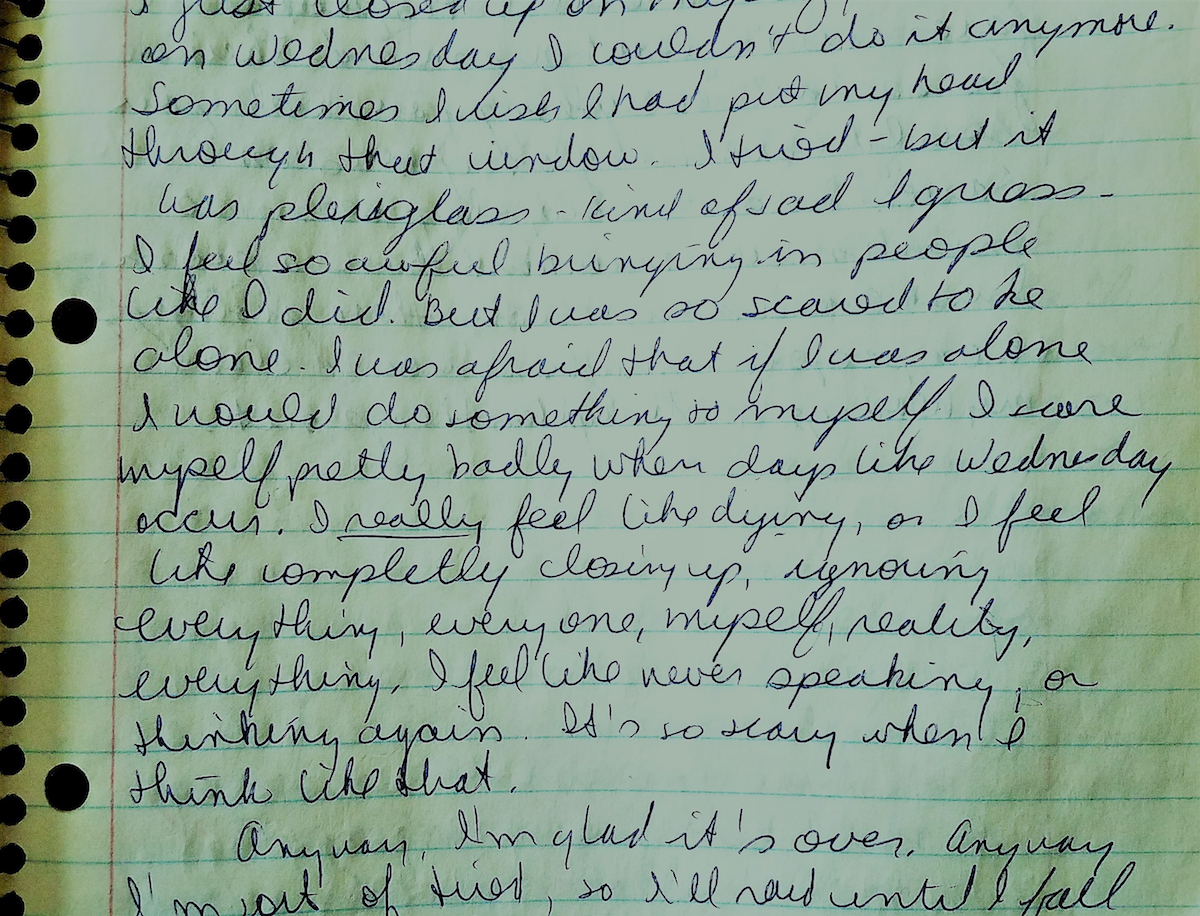

Once a week for two years, I saw a therapist, and though he tried to get me to talk, I just smiled back. “I’m fine,” I’d say, and pull a novel from my backpack — maybe Tender is the Night by Fitzgerald — and read a passage aloud to him. Maybe this one: “One writes of scars healed, a loose parallel to the pathology of the skin, but there is no such thing in the life of an individual. There are open wounds, shrunk sometimes to the size of a pin-prick but wounds still. The marks of suffering are more comparable to the loss of a finger, or of the sight of an eye. We may not miss them, either, for one minute in a year, but if we should there is nothing to be done about it.” All the while feeling the sharp pain of new cuts as I shifted arms; all the while hearing my inner voice urging me to just speak already but if you do you know you’ll sound stupid, right?; all the while thinking of my journal, an orange spiral notebook, and its pages scrawled with everything I needed to say.

In college, a one-night stand with a guy in my Anthropology class (my favorite class because the world suddenly opened up in strange complexity) kept me mute all semester. Despite the walk of shame back to my dorm the next morning, I was still hopeful that all the words he said when drunk (You are beautiful!), he also meant sober, but in class, my naïve heart constricted as he looked through me.

Who do you think you are that any boy might want you, need you, love you?

Nobody at all.

I got A’s on all my papers and exams for that class (an A+ on my final research paper on how Liberian women were subverting gender roles), but wound up with a B+ for the course: class participation counted for 20% of the final grade.

We often speak on impulse — I love you I hate you fuck you I’m sorry — wishing at times to take our words back, but when we speak aloud and are heard (though not necessarily listened to), we appeal to an audience for a response. Our noises are more than just bodily vibrations; our soundings help constitute our presence in the world.

Listen to me: what I have to say right now matters.

Silence, on the other hand, can become a default reflex. When my college boyfriend was abusive, when he wrapped his hands around my neck in anger or made stomach churning sexual demands, I was silent. When a graduate school friend assaulted me one night, thinking I was passed out, his hand sliding up my thigh, then his fingers pushing into me, I was silent. When my once-husband said I was unlovable because of my bipolar illness — too much, too crazy, too depressed, too sad, too manic, too hopeless — I was silent.

Dumbstruck. Silence might be misunderstood as the absence of anything to say — that is, the absence of an internal thinking-feeling-knowing self. But remember this: my fists were bunched beneath my thighs, my journals were full of words, and my arms were scrawled over with cuts and scars. Now, the scars remind me of how much I have to say and the imperative to say it.

Silence is a gathering force. Silence is immanence. What might I say when I start speaking? Think of Emily Dickinson and her intentional silence on the page. The dashes, the ellipses, and the white space offer pointed mediation between immanence and transcendence. Poem #1251:

Silence is all we dread.

There’s Ransom in a Voice—

But Silence is Infinity.

Himself have not a face.

Dickinson’s soundings are necessary though insufficient approximations of all she contains within, thus her audible silence:

—

...

.

Her poems and letters are sacred conversations: her inside-self speaks to her reader’s inside-self. “This is my letter to the World,” she writes, “That never wrote to Me —.”

Though her missives are not unrequited. After all, aren’t we reading them now? Don’t we sound her words with our inner voice and then annunciate them out loud? The Belle of Amherst is long dead, but her words resonate through our bodies, transcending material time: silence may be infinite, but her silence is infinitely audible.

Who do you think you are?

What did Whitman suggest? “I sound my barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world.”

I have no simple solution for how girls and women move from ruminating silence to barbaric yawping except to say this: I don’t raise my hand anymore nor wait to be called upon. Perhaps you think this impolite or ill-mannered? Not my intention. I speak with an unruly tongue, offering up my unquestionably right and occasionally (haha) wrong answers, my considered opinions and my harebrained ideas, my garrulous exuberance and my voluble outrage.

Circling back to the classroom: Allyson Jule, in her book, Gender, Participation, and Silence in the Language Classroom: Sh-Shushing the Girls, notes that boys talk nine times more than girls in the classroom and are encouraged, through subtle cues to do so, indicating that “linguistic space is something belonging to boys.” Critics argue that boys “act out more” so need to be called on by name; however, she says, “the overcorrection is still giving significance to the boys — even their naughtiness is more interesting than the girls' participation.”

Indecorous Naughtiness.

I no longer wait my turn because my turn might never come. Give the boys a chance. Nope, I’ll take my chances.

Last semester, my undergraduate Memoir Workshop — a workshop devoted to writing personal truth, to writing hard, difficult, joyous and transcendent stories — was comprised only of women students. Fifteen women. For the first few classes, my questions were met with studied silence despite my haranguing.

“This is your class! You have all the space!” I said.

One student raised her hand, and when she was done speaking, another, indecorous turn. They offered tentative answers and opinions in careful, hesitating speech, couched with disclaimers: maybe, possibly, I could be wrong, I’m probably wrong.

Who do you think you are to believe your words are right or matter?

“No more raising hands,” I finally said. “Speak when you have something to say and don’t be afraid to say something ‘wrong’ because we all fumble in uncertainty and insecurity. Be raucous, be rowdy, be respectful, but speak your minds.”

It took a few practice classes for my students to remember how to speak out of turn, and hedging and apologies when two students spoke at the same time.

You go.

No, you go.

No, you go.

No, you go.

(Are men equally gracious taking turns?)

Eventually, the women spoke up, but not over each other and sometimes pounding a declarative fist on the table or hooting in contagious laughter. And there was silence, but not from anxiety or fear. The women relished waiting in the weight of their possibility and immanence. What’s the word for a gathering of crows? A murder. Of starlings? A murmuration. Of wonder women? A clamor.

Necessary voices.